There’s a lot of confusing information available on managing small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO).

Even gastrointestinal experts can’t seem to agree on the best way to approach their diagnoses and treatment.

To update myself with the latest research in this area, I spoke with Dr. William Chey, a leading gastroenterologist researcher at the University of Michigan and world-renowned authority on food intolerance.

I asked Dr. Chey about how he diagnoses SIBO, his best recommended treatment and whether or not he thinks the low-FODMAP diet is effective.

His answers have been lightly edited for clarity.

Q. How would you best define what SIBO is?

Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth or SIBO is a condition where the communities of bacteria within the GI tract are displaced into the small intestine.

Because they’re in the small intestine, they can actually compete with the host for food. When, for example, carbohydrates are fermented by those bacteria, it can produce gas and chemicals that can trigger a whole variety of different symptoms like abdominal pain, bloating or diarrhea.

Because those bacteria are consuming the food instead of the host, the host may actually develop a malnutrition or malabsorption syndrome.

Q. Does the variation between symptom severity have to do with the type of bacteria causing the issue or the amount of bacteria?

We really don’t know, but I think there are lots of variables that could influence how severely affected a person is.

It might be related to the type or quantity of bacteria, or the location of the bacteria in the small intestine. There may also be a whole variety of host factors that likely play a role.

For example, your gut immune system functions differently than my gut immune system. How each reacts to that bacterial displacement or SIBO might be very different.

It’s not just the bacteria. It’s the host and how the host reacts to those bacteria that really determines the type of disease that one expresses.

Q. How do you screen someone who presents you with symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome (IBS)?

I think if you had 20 different experts, you’d get 20 different opinions.

For me, patients that come in with a combination of abdominal pain, bloating, flatulence and diarrhea are the ones that I’m most suspicious of having SIBO.

If they have another disease, like long-standing diabetes or a neuromuscular disorder like scleroderma or are on chronic acid suppressive therapy, my suspicions for the possibility of SIBO will be even higher.

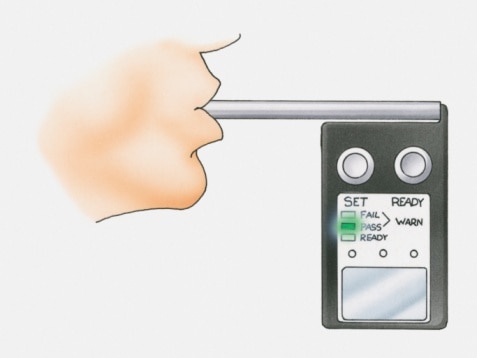

Q. Is there a particular breath test that they should do? How does that work?

There are different types of breath tests that can be used to identify SIBO, and you should understand what the pros and cons are of each.

In general, breath testing involves giving the patient sugar, most commonly lactulose or glucose. If there’s presence of bacteria in the small intestine, those bacteria will ferment that sugar and release hydrogen or methane.

This then gets absorbed across the lining of the small intestine and eventually excreted in the breath.

Neither the lactulose or glucose breath test is perfect. Here’s why:

Lactulose Breath Test

Lactulose is a synthetic disaccharide that is universally not broken down or absorbed by the human small intestine.

Now, the good news is if you have SIBO affecting any part of the small intestine, you’re likely to identify it with a lactulose breath test. The bad news is that once the lactulose gets to the colon it will ferment it just like bacteria will in the small intestine.

In other words, a lot of patients that have a positive lactulose breath test won’t turn out to have SIBO.

Glucose Breath Test

On the other hand, when you give an oral dose of glucose, it’s completely absorbed by the human small intestine. It’s gone by the time you get to the middle portion of the small intestine.

This means, you’re liable to miss cases of bacterial overgrowth that affect primarily the lower part of the small intestine.

So, it’s all a matter of whether you choose the risk of over-diagnosing or under-diagnosing SIBO.

What we really need are studies that sequentially sample throughout the small intestine to figure out the distribution of SIBO in different affected patients.

Q. Is there a way to determine SIBO without those breath tests? Some patients claim that there’s a difference in the timing or onset of symptoms after eating certain foods. Is this myth?

Unfortunately, it’s hard to use or rely upon symptoms as an accurate guide to identifying patients with SIBO.

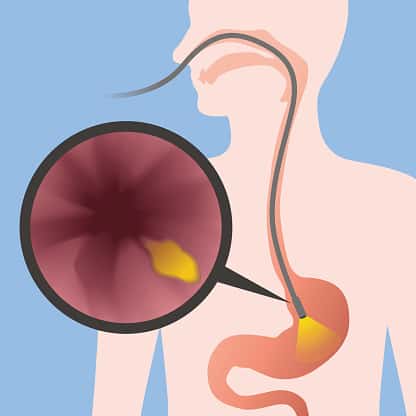

There are other tests that can be utilized. The “gold standard” right now is something called small bowel aspiration for quantitative culture.

That’s a fancy way of saying that when a gastroenterologist does an upper endoscopy, they suck up or collect a small amount of fluid from the small intestine. They then send that to the microbiology laboratory to determine how many bacteria can be identified.

The problem with this test is that you have to be very meticulous in the way that you collect the sample or you can accidentally contaminate it. Another big problem is that the standards of defining abnormal results are not universally agreed upon.

Q. For treatment, antibiotics are typically prescribed to go in and destroy the bad bacteria. What antibiotics work best?

Unfortunately, there are not very many large or well-done studies looking at the effectiveness of antibiotics in terms of treating SIBO.

The antibiotic that has the most rigorous research behind it is a non-absorbable one that starts with R and ends with N (we can’t write the name here on the blog otherwise we can get penalized by the search engines).

Because it’s very poorly absorbed, it concentrates in the lumen of the gastrointestinal tract, which is where we want the antibiotic to get rid of the excess bacteria in the small intestine.

Most of the studies show that around 60% of patients will be successfully cured or treated of their bacteria overgrowth with this particular antibiotic.

There are other antibiotics that have been studied less rigorously, which show similar ranges of success.

Q. Are there alternative herbal antibiotics, like iodine drops, that have been proven effective?

None that have been studied.

For example, people have been talking a lot about apple cider vinegar. Taking an acid like this may have an impact on pH in the very upper part of the small bowel.

But bicarbonate secreted by the pancreas is going to neutralize any acid, so it’s hard to believe it will have much effect in the entire small intestine.

There’s also been a lot of discussion about the antibacterial effects of garlic and ginger, but they’ve not been well-studied in rigorous research trials.

For now, I wouldn’t turn to any of these remedies as a primary solution for SIBO, but there are circumstances where a patient may not have any other options.

Q. Would you recommend taking antibiotics and probiotics at the same time?

Some people say that adding a probiotic consisting of “good bacteria” might restore the balance of bacteria that would help to prevent the development of SIBO.

Remember that SIBO in part is related to the location of bacteria and alterations in the communities of bacteria that live inside the GI tract. There is, theoretically, the possibility that adding beneficial bacteria might restore that balance.

On the other hand, other people think that you shouldn’t use probiotics because you’re already dealing with a condition where there’s excess bacteria in the wrong place.

Currently, I’m more in this latter group, although I’m open-minded to the possibility that probiotic supplements might eventually be proven to be beneficial.

That said, it’s important to remember that in the United States, most probiotics are regulated as food supplements, not as drugs.

There is no guarantee that when you buy a probiotic supplement it will contain any viable bacteria at all. In fact, most of the stuff that people are buying doesn’t contain any live bacteria.

And does it even make sense that a particular strain of bacteria will have the same effect in every person who has a different diet, genetics and communities of bacteria in their GI?

I think that until we are able to choose the right probiotic or prebiotic for the right individual, they’re never going to be that terribly effective.

Q. What’s your opinion about the low FODMAP diet for treating SIBO and IBS?

Up until the low FODMAP diet, there was a tremendous amount of scepticism about the value of diet therapies for irritable bowel syndrome (IBS).

In fact, when I was a fellow in gastroenterology some 25 years ago, I was taught that there was no diet therapy that was effective for IBS. We were told that the best thing to do was to tell patients to eat small and more frequent meals, avoid fatty or greasy foods and eat more fiber.

Now, it turns out that a bunch of those things are ineffective, and some can actually make people worse.

But over the past 10 years, there’s been an explosion of not only interest but also scientific research that shows a couple things:

- Most patients’ symptoms are triggered by eating a meal.

- A number of diet therapies, including the low FODMAP diet, is effective for a subset of patients with IBS.

Now, does it make everybody better? No, but it makes at least half the patients better. Pretty consistently those with IBS will report improvements in pain and bloating with the low FODMAP diet.

The diet consists of three phases. All the research is currently focused on the elimination phase, which only determines whether a person is sensitive to FODMAPs or not. It’s not the end. It’s only the beginning.

If a person benefits from the elimination phase, they need to go through a phase where they reintroduce foods containing FODMAPs to determine their sensitivities.

Then they can use that information to personalize or modify their diet to make it more inclusive and less restrictive. We call these three phases ESP: eliminate, determine sensitivities, personalize the diet.

Q. Do you have any tips for finding knowledgeable gastroenterologists or doctors?

Most that are experienced and commonly take care of patients with functional GI immobility disorders are going to be experts at managing SIBO.

You’ll also want to check whether they do breath testing. Because if they don’t, they can’t possibly be that interested or experienced in taking care of SIBO, right?

To learn more about Dr. Chey’s work, check him out on Twitter or visit his Michigan Medicine profile.

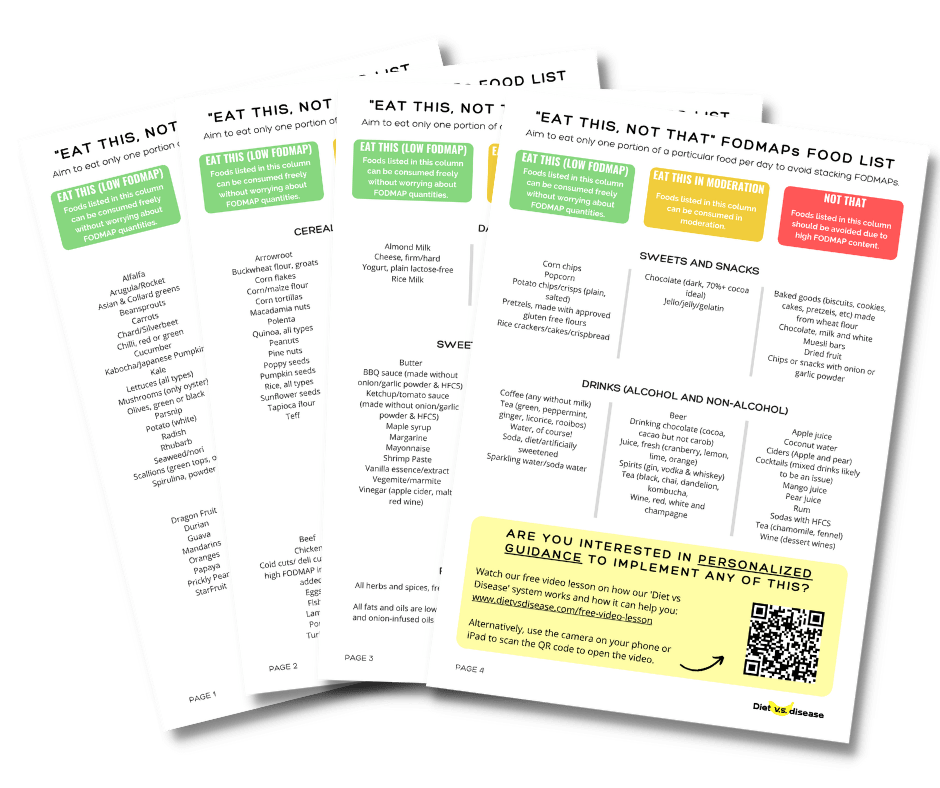

What Can And Can’t I Eat On The Low FODMAP Diet?

Often it’s easiest to start with this giant list I’ve made of what foods to eat, and what foods to avoid when following a low FODMAP diet.

It’s based on the latest published FODMAPs data (1, 2, 3, 4, 5).

Print or save to your phone to use as a quick-reference guide when shopping or cooking. I’ve attempted to list foods in both US and UK/Aus names, with US first.

I’ve included a screenshot of the first page below. But the full PDF is 4 pages and suitable for printing. To download it simply tap the box below and it will then be emailed straight to you – it’s free!