Fiber is an essential part of a healthy diet, especially for optimal digestive health.

But conflicting information about what type of fiber and how much to eat can be confusing.

This article breaks down what fiber is and how it can protect you from digestive disorders and discomfort.

What Is Fiber?

Fiber is a type of carbohydrate, alongside sugar and starch.

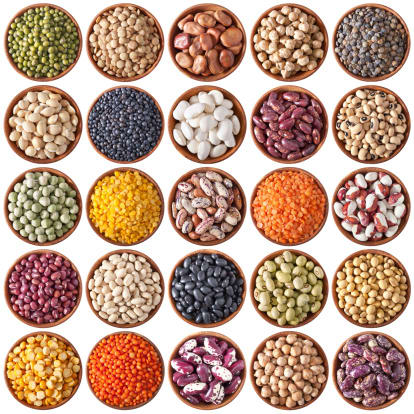

It’s found in fruits, vegetables, nuts, seeds, whole grains and legumes.

Unlike starchy carbohydrates and sugars, fiber contains chemical bonds that can’t be broken down by digestive enzymes in the body. This is why it reaches the large intestine (the gut) mostly undigested.

While the bulk of fiber ends up being excreted, some of it will be digested by gut bacteria in a process called fermentation. This produces certain fatty acids and gas.

Summary: Fiber is a type of carbohydrate that is difficult for the body to breakdown and digest. Most is excreted as waste, but some is fermented in the large intestine.

What Are the Different Types of Fiber?

Fiber is classified in a number of ways. It’s most often broken down into soluble and insoluble fiber.

Soluble Fiber

Soluble refers to a substance that dissolves in water and forms into a gel. If you’ve ever mixed chia seeds with liquid, you may have seen this process in action.

Soluble fiber is commonly found in foods such as oats, barley, citrus fruits and legumes. It’s generally readily fermented in the gut.

An increased intake of soluble fiber has been shown to lower cholesterol, maintain heart health, regulate blood sugar levels and reduce the risk of type 2 diabetes (1).

Insoluble Fiber

Insoluble fiber does not mix in water or form a gel.

It’s also found in many whole grains, fruits and vegetables, but is not as easily fermented as soluble fiber.

An increased intake of insoluble fiber has shown to help with weight control and regulating bowel movements. It may also improve heart health and blood sugar regulation (1).

Resistant Starch

Resistant starch also acts as a type of fiber.

It has the same chemical bonds holding them together as regular starch and can be broken down by digestive enzymes. However, they’re able to avoid digestion, too, hence the name resistant starch.

Resistant starches are naturally present in foods such as whole legumes and slightly green bananas. Other foods, like pasta, produce resistant starch when they are cooked and then cooled.

Resistant starch has many of the same health benefits as soluble fiber. It can promote good gut bacteria growth and appetite control, reduce insulin resistance and produce compounds called butyrate that are beneficial to colon health (2).

Other Classifications

Fiber classification can be broken down even further to include:

- Dietary (occurs naturally) and functional (added to food products)

- Viscous (forms a thick gel) and non-viscous (does not gel)

- Fermentable (digested by gut bacteria) and non-fermentable (not readily fermented)

Summary: Fiber is classified as soluble (dissolves in water), insoluble (does not dissolve in water) or resistant starch. It can be further classified by its origin (dietary or functional), whether it gels (viscous or non-viscous) and how it is processed in the gut (fermentable or non-fermentable).

How Does Fiber Affect Digestive Health?

In addition to its many metabolic health benefits, fiber also plays an important role in digestive health.

It does so by the following actions:

- Normalises frequency of bowel movements: This occurs by drawing water into the gastrointestinal (GI) tract to soften stools, and by increasing bulk, which stimulates faster passage through the GI tract (1).

- Acts as a prebiotic: Prebiotics are substances that “feed” gut bacteria to help them grow. Fiber is a well-known prebiotic (3).

- Produces short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs): The fermentation of fiber in the large intestine produces SCFAs, mainly acetic acid, propionic acid and butyric acid. Butyric acid in particular aids gut health (5).

Summary: Fiber is important for digestive health because it helps regulate bowel movements, feed good gut bacteria and produce short-chain fatty acids.

Does Fiber Protect Against Digestive Disease and Disorders?

Fiber encourages the growth of “healthy” gut bacteria (the gut microbiota), while inhibiting the growth of pathogens in the large intestine.

For these reasons it may protect against certain digestive disorders and diseases. Here’s how fiber does just that.

Short-Chain Fatty Acids and Digestive Health

Short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) contain six carbon molecules or less.

They are produced when fiber is fermented in the gut. SCFAs can lower the pH of the gut (which alters its acidity), inhibiting the growth of acid-intolerant pathogens. This in turn may protect against infection and diarrhea (5).

SCFAs are also thought to improve muscle tone and blood flow in the GI tract (5).

The production of SCFAs plays an important role in the makeup of the gut microbiome. Likewise, the composition of the microbiome can also affect the production of SCFA – they essentially work together to maintain digestive health (6).

Fiber and the Gut Microbiome

The makeup of the gut microbiome is attributed to a host of health benefits and disorders.

It can have a significant effect on digestive health. Imbalanced microbiomes are linked to irritable bowel syndrome, inflammatory bowel disease and colorectal cancer (3, 4).

Fiber can affect the composition of the gut microbiota by altering fermentation, colony size and strains of bacteria.

The amount and type of fiber in the diet, as well as the acidity of the GI tract and stool transit time (which are also regulated by fiber), heavily influence the microbiome. This is why fiber is so important (3, 4).

In fact, just by altering the fiber content in our diet, we can produce specific microbiota outcomes. This is not yet fully understood, but there is a lot of exciting research happening in this area.

Fiber and Colorectal Cancer

Diets high in fiber are associated with lower risk of colorectal cancers.

Some studies suggest that for every 10 grams of dietary fiber consumed per day, colorectal cancer risk declines by 9-10% (1).

Interestingly, it appears that fiber from cereal grains is more protective than fiber from fruits and vegetables (1).

This observed reduction in cancer risk is likely due to fiber’s role in helping keep bowel movements regular so that stool spends less time in the GI tract.

Fiber and Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD)

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) includes a number of diseases that cause chronic inflammation of the digestive tract.

Some studies suggest a high-fiber diet can reduce the risk of IBD.

It’s believed that the effect of fiber on the microbiome and the anti-inflammatory effects of butyrate (a type of SCFA) may contribute to reduced incidence and relapse of IBD (7). It may also play a protective role against colorectal cancer in susceptible IBD patients (8).

Fiber consumption often needs to be altered for people with IBD – you can read more about those diets here.

Fiber and Diverticular Disease

When muscles of the GI tract lose strength they can bulge out into pockets causing diverticular disease.

Increased fiber consumption may help prevent inflammation of these pockets, a condition called diverticulitis. Evidence in this area is weak, yet a high-fiber diet is still recommended as it doesn’t make things worse and has other health benefits (9, 10).

More information about diverticular disease and diet can be found here.

Summary: A fiber-rich diet contributes significantly to a healthy gut microbiome. It may also protect against certain digestive diseases and disorders like colorectal cancer, IBD and diverticular disease.

Fiber and IBS

The evidence for additional fiber to treat irritable bowel syndrome is a mixed bag.

Two recent studies examined the effects of fiber on IBS symptoms in over 2,000 patients. Researchers concluded that soluble fiber, but not insoluble fiber, improved IBS symptoms (11, 12).

It’s possible that fermentation of soluble fiber in the gut will actually exacerbate symptoms. If you decide to trial soluble fiber, you should gradually add it to your diet over a few weeks. You can then determine if it’s beneficial for you.

IBS symptoms can often be relieved by following a diet low in fermentable carbohydrates called FODMAPS. Some foods high in soluble fiber such as beans and legumes are also high in FODMAPS. This should be taken into account when choosing high-fiber foods.

You can read more about relieving IBS symptoms here.

Summary: Soluble fiber may help some sufferers of IBS, but not all. To trial, soluble fiber should be introduced to the diet gradually.

Fiber and Constipation

People who suffer from chronic constipation will likely benefit from increasing fiber in their diet (13).

Insoluble fiber attracts water into the GI tract and adds bulk to stools, while soluble fiber can help soften stools. Both contribute to making stool passage and excretion easier.

If you are currently experiencing constipation, introducing fiber or fiber supplements may cause initial discomfort until the “blockage” is cleared. Continual consumption of fiber will help keep bowel movements regular and prevent the reoccurrence of constipation (14).

If diet alone does not help with symptoms, fiber supplements may be beneficial.

A multi-study analysis found that fiber supplementation was effective in treating chronic constipation in 5 out of 7 studies, and in all 3 studies looking at fiber’s role in treating constipation-predominant irritable bowel syndrome (IBS-C) symptoms (15).

These studies were all small in size and short in duration, which means more research is needed in this area.

If a fiber supplement is required, psyllium is likely the best to treat constipation (14).

You can find more tips on relieving constipation here.

Summary: Increasing fiber content can likely help relieve chronic constipation. Fiber supplements may be useful if sufficient fiber cannot be consumed in the diet.

Fiber and Diarrhea

A high-fiber diet may also help with diarrhea.

It does so by adding bulk to the stool and absorbing excess water present in the GI tract.

If a supplement is required, psyllium is preferred. It can improve stool formation and reduce the severity of chronic diarrhea (16).

Unfortunately, there is a lack of research on fiber and diarrhea, so other fiber supplements cannot be recommended at this time.

More tips on how to manage diarrhea can be found here.

Summary: Dietary fiber can help manage chronic diarrhea. Psyllium supplements may improve symptoms. There is still a lack of evidence regarding the effectiveness of other types of fiber supplements.

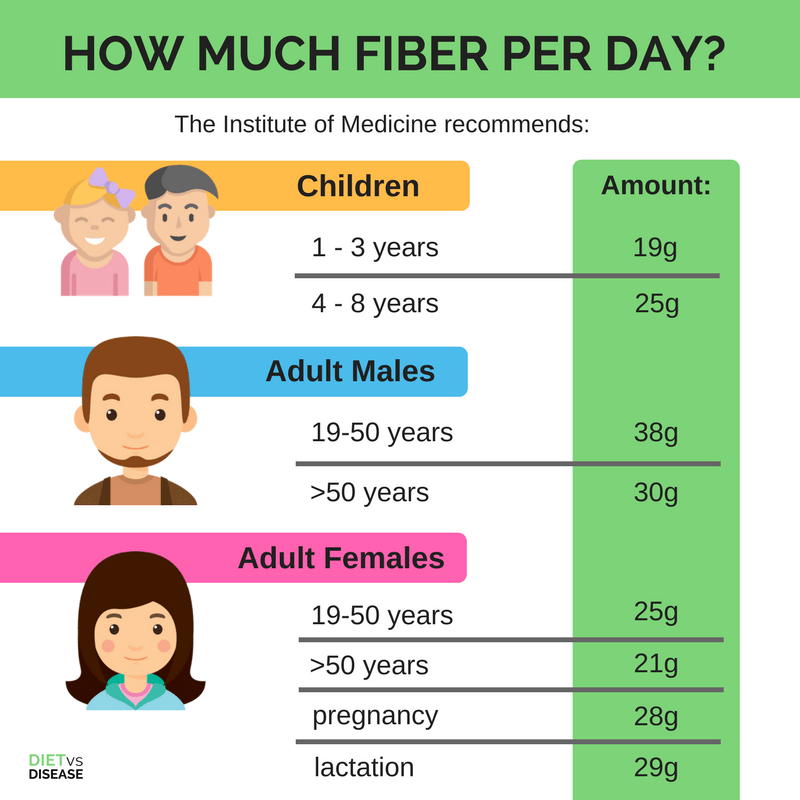

How Much Fiber Per Day?

The Institute of Medicine recommends this much fiber per day (17):

Children

- 1-3 years: 19g

- 4-8 years: 25g

Adult Males

- 19-50 years: 38g

- >50 years: 30g

Adult Females

- 19- 50 years: 25g

- >50 years: 21g

- pregnancy: 28g

- lactation: 29g

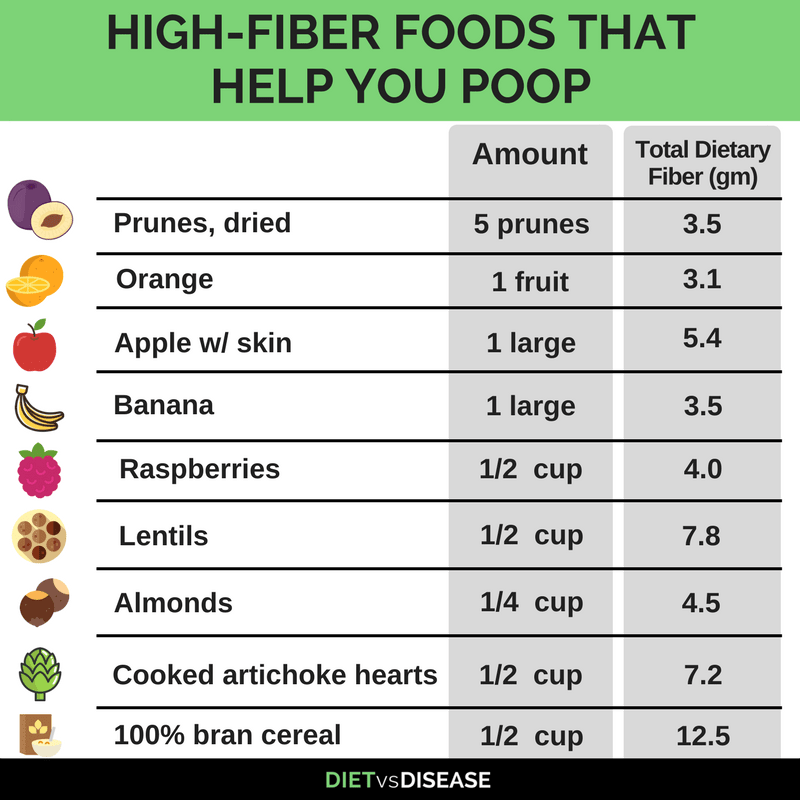

High-Fiber Foods That Help You Poop

As mentioned above, both soluble and insoluble fiber foods will help you poop.

Legumes, fruits, vegetables, whole grains, bran products, nuts and seeds are all high in fiber.

The best sources include berries, fruits and non-starchy vegetables with their skins intact, and nuts.

Is There Such a Thing as Too Much Fiber?

There is currently no upper tolerable limit set by the Institute of Medicine for fiber intake (17).

However, simply eating too much fiber all at once may cause digestive discomfort.

This is especially true if your current diet is low in fiber. For this reason introducing fiber into the diet should be done over a period of a few weeks and spread out over meals.

If you eat a low-fiber diet, aim to take the following steps:

- Add high-fiber foods gradually

- Drink plenty of water

- Choose from a variety of fiber-rich foods, so that you get both soluble and insoluble fiber

If you have a digestive disorder such as IBS or IBD you should speak with your dietitian or doctor to make sure you do not exacerbate symptoms.

Summary: By gradually adding high-fiber foods into your diet, you will likely avoid experiencing any side effects. Those with digestive disorders should be cautious when increasing their fiber intake.

Should I Take a Fiber Supplement?

Naturally occurring fiber from whole foods is the best way to incorporate fiber into the diet.

If you are unable to add enough through your diet, you may consider a fiber supplement. Alternatively, you can try adding bran, psyllium, and/or flaxseed to your meals.

Psyllium is the fiber supplement with the most supporting evidence to treat both constipation and diarrhea and, in some cases, IBS.

Would you like more information on how to start a low FODMAP diet?

Tap the blue button below to download our “Eat This, Not That” list as well as additional resources for IBS and digestive issues (it’s free!)