Inflammatory bowel disease refers to long-term inflammation in the digestive tract.

It’s a serious condition that can cause many dangerous health issues.

Fortunately, it can be very well-managed with the right approach.

This article explores what you need to know about treating inflammatory bowel disease… without all the scientific jargon.

What is Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD)?

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) refers to a group of long-term inflammatory conditions that affect the digestive tract.

The most common types of IBD are:

- Ulcerative colitis: Found in the innermost lining of your colon and rectum. It produces inflammation and ulcers.

- Crohn’s disease: Found anywhere in the digestive tract (from mouth to anus), but usually within the small intestine.

- Microscopic Colitis: An inflammatory condition of the colon, broken down into two forms—collagenous and lymphocytic colitis.

There are sub-types of these diseases based on where it affects the gastrointestinal tract.

At this time there is no known medical cure for IBD, but there is a range of treatment options to reduce inflammation and manage symptoms.

Unfortunately, inflammatory bowel disease now affects over 1 million people in the US and 2.5 million people in Europe (1).

Summary: Inflammatory bowel disease is a group of inflammatory conditions that affect the gastrointestinal tract. Ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease are two main types.

Symptoms of IBD

Symptoms vary depending on the type and severity of IBD, and may change over time.

When inflammation is severe, IBD is considered active and symptoms are worse.

When inflammation is low, IBD is considered in remission and the patient is usually symptom-free.

Common symptoms include several of the following:

- Chronic diarrhea

- Chronic constipation

- Fever

- Abdominal pain, bloating and cramping

- Fatigue

- Urgency to move bowels

- Blood in stool

- Dehydration

- Reduced appetite and/or unintentional weight loss

- Anemia (too few red blood cells)

- Night sweats

- Loss of normal menstrual cycle

Note that these symptoms overlap with those of many other conditions, which is why there is a thorough procedure to follow for your doctor to diagnose it.

Summary: Symptoms of IBD vary widely and depend on the severity of inflammation, though they are usually digestive related. Patients who become symptom-free are classified as in remission.

IBS vs IBD

It’s important to make the distinction between the two acronyms.

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is a functional digestive disorder. That is, there is no clear physical issue that causes the symptoms. This is why it’s called a syndrome rather than a disease.

Diet and lifestyle changes are typically adequate to treat it. Additionally, IBS is common, thought to affect between 13-20% of those in the US, UK and Australia (2, 3).

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) refers to physical inflammation of the digestive tract, particularly in the large intestine (called the bowel or colon). It’s this inflammation that causes the symptoms.

It’s far less common than IBS but also much more severe. Left unmanaged it can cause irreversible damage and may be life-threatening.

Summary: IBS is a functional disorder that is not related to physical changes in the digestive tract. IBD is a disease characterised by physical damage to the digestive tract and can cause serious complications.

What Causes IBD?

IBD is complex and the specific cause still remains unknown.

Those with a family history are more likely to develop it, so there is a clear genetic component.

This genetic predisposition shares similarities to autoimmune conditions such as type 1 diabetes and celiac disease (4).

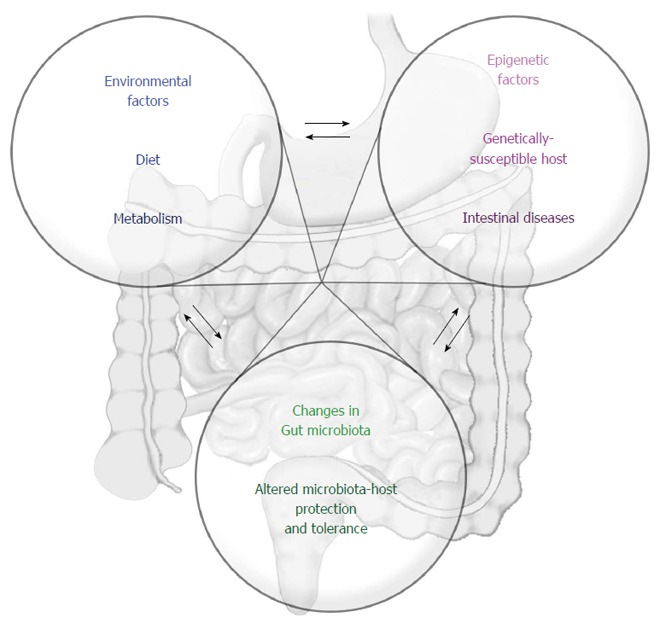

IBD is also linked with a reduced diversity of bacteria in the gut, know as the gut microbiota. In particular, an increase in bacteria with pro-inflammatory affects, and a decrease in bacteria with anti-inflammatory affects (5).

Environmental factors are also likely contributors, such as stress levels, smoking, eating patterns and other lifestyle choices that can influence gut bacteria (6, 7).

Researchers now believe an interaction between unfavorable genetic and environmental factors is what triggers a harmful immune response against the digestive tract (8).

Interactive factors that lead to the development of inflammatory bowel disease. Click to enlarge.

Summary: The cause of IBD remains unknown but it’s thought to be a combination of genetics and environmental factors.

Conventional IBD Treatment

There is no cure for IBD.

The aim for treatment is to reduce inflammation that drives symptoms. For this reason treatment methods vary depending on the IBD type and severity (9).

Medication

Medication is usually the first approach (10).

This includes powerful anti-inflammatory drugs and immune system suppressors.

Other medication may also be required:

- Anti-diarrheal medications to add bulk to stools

- Pain relievers for mild pain

- Iron supplements if individuals experience anemia from chronic bleeding

- Vitamin supplements for deficiencies

Surgery

Surgery for treating IBD is not uncommon.

In fact, 20% of individuals with ulcerative colitis and up to 80% of individuals with Crohn’s disease will eventually need surgery (11).

In many cases patients choose to have surgery because symptoms become unbearable. They may do well on medication for a while, but then for unknown reasons they stop responding.

Surgery can cure ulcerative colitis as inflammation only occurs on the top layer of the intestinal lining. Unfortunately it cannot cure Crohn’s disease as inflammation can affect all layers of the intestine, and can spread through the entire digestive tract (from mouth to anus).

Summary: Medication is the first line of treatment for IBD, followed by surgery in more severe cases or where medication fails. Surgery can cure ulcerative colitis but not Crohn’s disease.

General Diet Recommendations for IBD

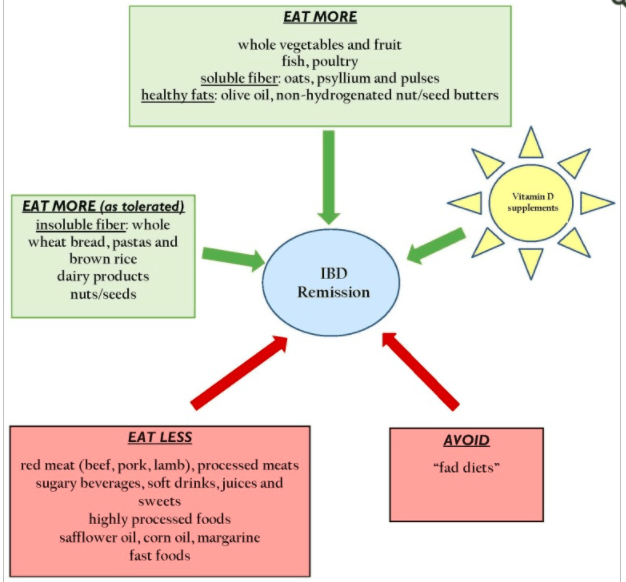

A very recent review study concluded these are the main dietary consideration to maintain remission (free of symptoms):

Image source. Click to enlarge.

However, many patients state these recommendations are over-simplified and often ineffective. And it makes sense that a one-size-fits-all approach does not work for IBD.

As a result there are many unique IBD diets that have emerged which we’ll look at in the next section.

Nutrient Deficiencies and Trigger Foods

Although diet is not a cause of IBD, it plays a critical role in treatment.

One of the main reasons is because patients are at very high risk for nutrient deficiencies as the digestive system is not functioning properly.

The most common deficiencies are (12):

- iron

- zinc

- vitamin K

- folic acid

- selenium

- vitamin D

- B12

- vitamin B6

- vitamin B1

Recommended eating patterns for patients must account for these increased deficiency risks.

Foods known to trigger digestive stress should also be minimized. This includes large portions of high fiber foods (eg lots of watermelon), fatty (fried) foods, alcohol and caffeine (13).

Summary: Diet plays a critical role in treating IBD, particularly for preventing nutrient deficiencies and minimizing trigger foods. There are general eating guidelines for IBD patients, although many feel these are too generic and not always effective.

IBD and Specific Diet Plans

Specific diets have recently emerged with claims they help treat IBD.

The general theory is that they keep gastrointestinal inflammation to a minimum, which helps with pain and symptom management.

This is a look at the main ones:

A Low Fiber or Low Residue Diet

This eating pattern is typically prescribed for those in an acute phase of IBD (opposite of remission).

That is, when symptoms are flaring and active.

The idea is to limit the foods that add bulk to stools so that they pass as easy as possible through the digestive tract. It works very well as a short-term solution and is often prescribed in hospital and for a certain time period after hospital discharge.

In severe cases parenteral nutrition will be used first, which nourishes patients with nutrients direct into the bloodstream. This gives the bowel complete rest (no digestive process is required).

The Specific Carbohydrate Diet (SCD) for IBD

The Specific Carbohydrate Diet (SCD) is an eating pattern that restricts complex carbohydrates.

These are larger carbohydrate molecules that can be harder to digest and are thought to contribute to symptoms.

Early studies suggest SCD may help manage IBD, particularly in children. The most recent study looked at 12 children with mild to moderate ulcerative colitis or Crohn’s disease following the SCD for 12 weeks.

Researchers found five participants (50%) achieved remission after 2 weeks and eight participants (80%) at 12 weeks (two participants dropped out in the beginning). Small changes in fecal bacteria and a reduction in markers of inflammation were also seen (14).

It looks promising, but note that it was ineffective for 2 patients, while 2 others were unable to maintain the diet and dropped out.

Theses results support findings in similar studies on children with IBD. They typically find the SCD is useful, but it’s not uncommon for patients to have difficulty sticking with the diet long term (15, 16).

As for adults, an online survey of 417 IBD patients found that about 33% of responders reported remission when on the SCD for a minimum of two months (17).

Overall the SCD shows promise and could certainly be worth a try after speaking to your doctor or dietitian. Just know that major organisations such as The Crohn’s & Colitis Foundation of America (CCFA) do not promote any particular diet.

Anti-Inflammatory Diet for IBD (IBD-AID)

The Anti-Inflammatory Diet for IBD, also known as IBD-AID, was derived from the Specific Carbohydrate Diet (SCD).

However, it contains a few ‘modifications’ based on more recent research into the human gut microbiome (gut bacteria). We now know that IBD patients experience changes in their gut bacteria compared to the general public (6, 7).

IBD-AID is split into four basic parts that need to be part of your daily diet:

- Prebiotics

- Probiotics

- Good balanced nutrition

- Avoidance of certain foods

Following these guidelines is said to promote a nutrient-dense diet while restoring balance between the “good” and “bad” bacteria in your gut. This should help manage IBD, theoretically.

There was only one study I could find to support these claims, which was a case series of 27 IBD patients (both ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease) who tried the IBD-AID.

There was 24 patients who had a good response, and 3 with a mixed response. Those who followed IBD-AID for 4 weeks or more were able to discontinue at least one of their IBD medications (18).

Just note that this was not a controlled trial where those following the diet were tested against those not on the diet (placebo group), so better level evidence is required before any strong recommendations can be made.

The University of Massachusetts has more detailed information on the IBD-AID diet here.

The Low FODMAP Diet for IBD

The low FODMAP diet is a type of elimination diet.

FODMAPs are short-chain carbohydrates known to cause digestive issues in people with irritable bowel syndrome (IBS).

The diet involves eliminating foods high in FODMAPs for between 3-8 weeks before strategically reintroducing them back into the diet. This allows you to identify what specific FODMAPs don’t agree with you.

It may be useful for IBD patients who have overlapping IBS symptoms, but there is no convincing research (yet) that it helps reduce gastrointestinal inflammation. Therefore, there is no clear evidence it helps treat IBD specifically and should be used with caution (19).

Note that in some instances, such as Crohn’s disease with strictures, a low FODMAP diet could do more harm than good. Always talk with your doctor or dietitian first.

The Maker’s Diet

The Maker’s diet is based on the Old Testament laws of the bible and is also known as the Bible diet.

The author says the diet is responsible for curing his Crohn’s disease at the age of 19, but it’s targeted at the general population as well.

There have been no studies conducted on this diet, and certainly not for treating IBD. The author also creates supplements and products that make extreme health claims, which the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has cautioned and threatened with fines.

I cannot recommend you try the Maker’s diet.

Summary: The SCD diet appears promising for long-term IBD management, with a lot of early research being done. IBD-AID and the low FODMAP diet could be worth consideration as well, while the Maker’s diet is not recommended.

Supplements and Probiotics For Treating IBD

There are few supplements and probiotics that have been studied for IBD treatment.

This means the current evidence is in its early stages and often contradictory.

For example, a survey study on New Zealand Crohn’s disease patients found that many foods perceived as helpful to some were perceived as harmful to others, which adds to the confusion (20).

Here is what shows the most promise:

Curcumin (Turmeric)

Curcumin is the active ingredient in the spice turmeric.

It’s known to have powerful anti-inflammatory effects at high doses and should theoretically help with IBD.

A 6-month clinical trial found that 2 grams of curcumin daily alongside standard treatment for ulcerative colitis reduced intestinal inflammation and improved symptoms.

Curcumin use reduced recurrence of IBD symptoms, but these protective effects disappeared when curcumin was stopped (21).

These findings support what was observed in an earlier study of both ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease patients (22).

The clinical trial needs to be repeated before we can make any strong conclusions, but it’s certainly a promising area to consider.

Probiotics

Probiotics are “good” bacteria that can improve our health, particularly digestive health.

Most believe they may improve IBD by regulating the inflammatory response or altering gut bacteria composition. Researchers are now trying to determine which type of probiotics (which bacterial strains) are most beneficial (19).

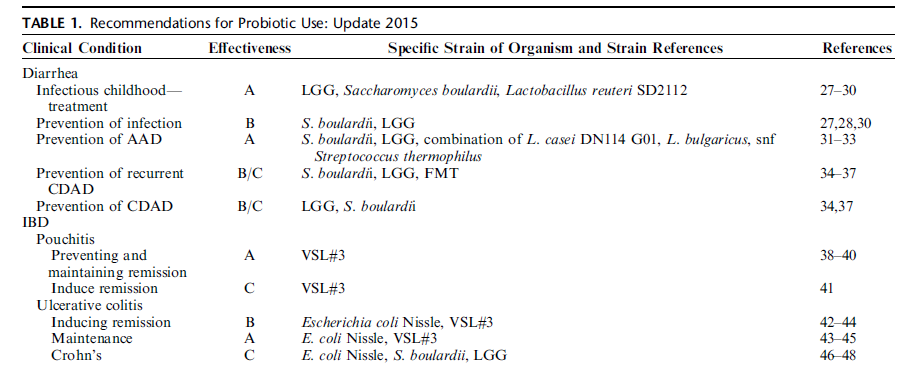

Several probiotic varieties were identified as the best options for IBD at the 2015 Yale University workshop (23):

- Ulcerative colitis: E. coli Nissle and VSL#3. They appear more useful for maintaining remission than treating symptoms.

- Crohn’s disease: E. coli Nissle, S. boulardii and Lactobacillus rhamnosus (also called LGG). The evidence for these is much weaker than for treating ulcerative colitis.

These recommendations can be viewed in the table below. Note that recommendations are given as A, B or C ratings based on the quality of studies done.

Click to enlarge.

Summary: Few supplements have been tested for IBD treatment. Curcumin is promising, as are several strains of probiotics depending on what type of IBD you have.

IBD and Restroom Access

Sometimes those with IBD will need to use a bathroom urgently.

Obviously this can be quite stressful when out in public.

Fortunately, many countries have cards or laws in place that allow IBD patients to gain access to a bathroom when needed.

- USA: The Restroom Access Act or Ally’s Law has been passed in several states. It allows those with IBD to use employee restrooms when no public restrooms are available.

- Australia and UK: There is a Can’t Wait Card that individuals can show when they need urgent access.

Inflammatory Bowel Disease Treatment: Summary

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is a serious condition that requires strict medical treatment.

Diet changes are required alongside medicine to manage symptoms, correct nutrient deficiencies and reduce the risk of recurrence.

The most promising dietary patterns for preventing flare-ups are the SCD and IBD-AID, but there is still not enough research to make any strong conclusions. The low FODMAP diet is also an option if there is an overlap of IBS.

Curcumin supplements and certain probiotics may help too, but always speak with your doctor first.

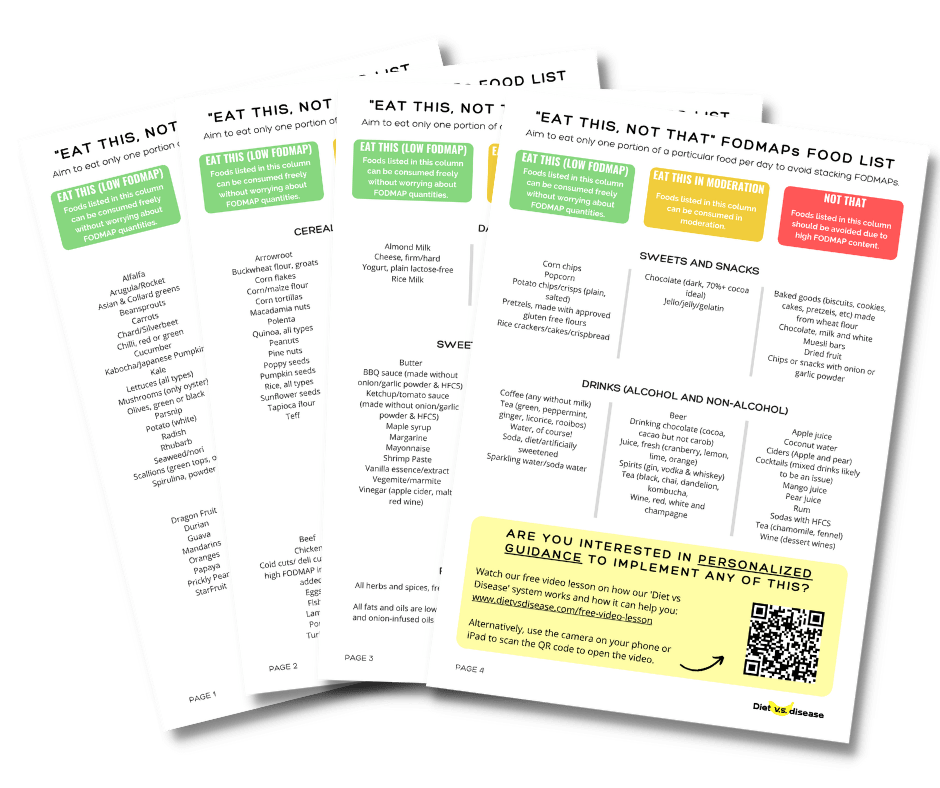

What Can And Can’t I Eat On This Diet?

Often it’s easiest to start with this giant list I’ve made of what foods to eat, and what foods to avoid when following a low FODMAP diet.

It’s based on the latest published FODMAPs data (1, 2, 3, 4, 5).

Print or save to your phone to use as a quick-reference guide when shopping or cooking. I’ve attempted to list foods in both US and UK/Aus names, with US first.

I’ve included a screenshot of the first page below. But the full PDF is 4 pages and suitable for printing. To download it simply tap the box below and it will then be emailed straight to you – it’s free!

Further reading:

The Best Diet For Ulcerative Colitis: Splitting Fact From Fiction

Dietary Treatment of Crohn’s Disease: A Review of the Evidence