One of the most cutting-edge areas of research involves the ‘gut-brain axis’ – the connection between the brain, gut, and microbiome and its potentially huge influence over our health.

Only recently have scientists started to better understand the gut-brain-microbiome axis and how it can impact not only physical and digestive issues, such as irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), but also mental health conditions like depression and anxiety.

This article investigates our current understanding of what the gut-brain axis is, the role of the gut microbiome, and how our physical and mental health can be compromised when communication between one or more parts along this axis becomes faulty.

What is the Gut-Brain Axis?

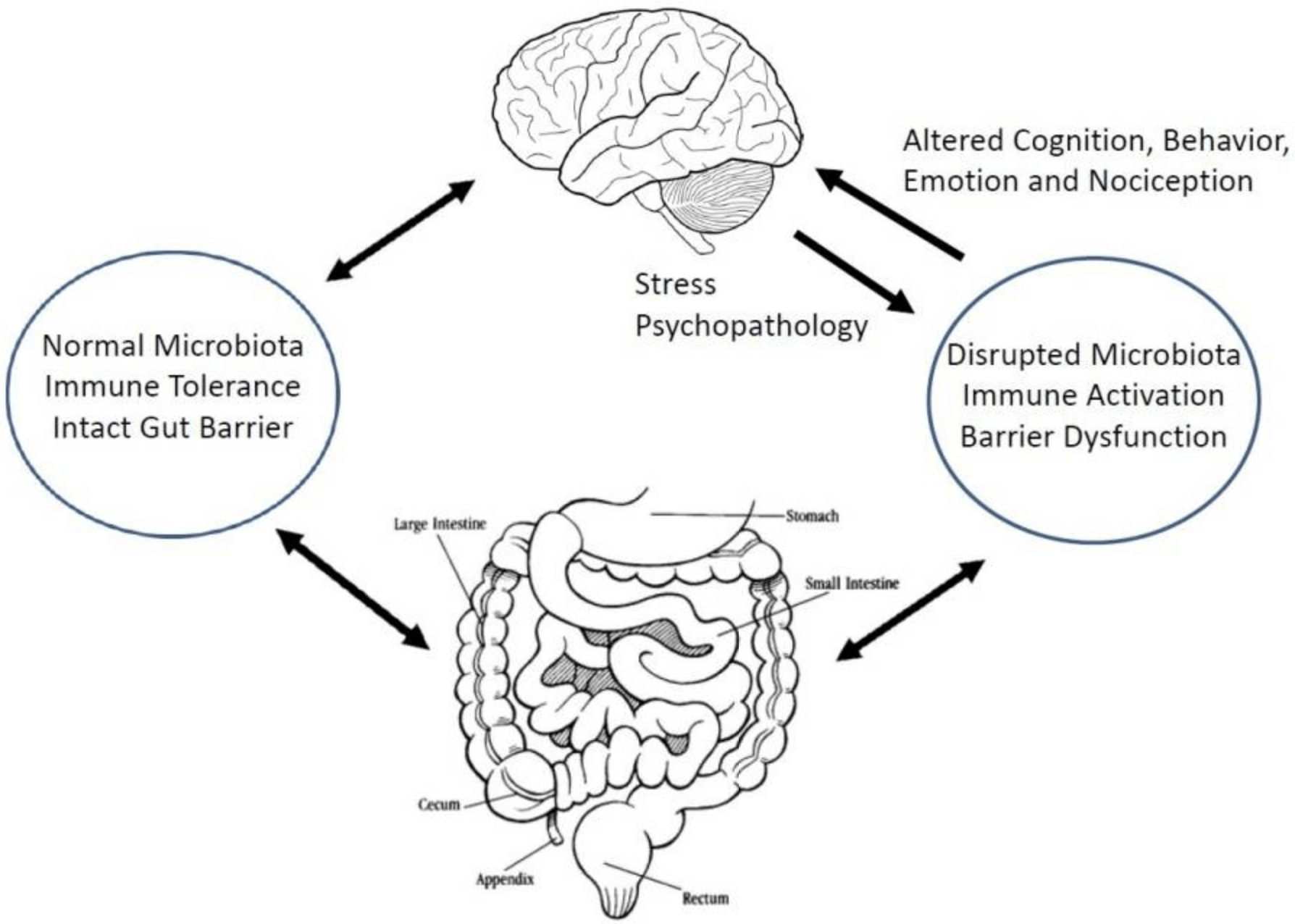

The gut-brain axis (or gut-brain connection) describes the two-way (bi-directional) connection and communication between the gut and the brain (1).

The gut and the brain are connected through the largest nerve in the body, called the vagus nerve, and they communicate both ways through this nerve connection.

There are also a number of additional pathways that are involved in the complex functioning of the gut-brain axis including communication through various chemical messengers, the endocrine system, gut hormones and neurotransmitters (2, 3).

Many of these hormones and neurotransmitters are actually made in the gut, such as gamma aminobutyric acid (GABA), dopamine and serotonin and gut bi-products of carbohydrate fermentation such as short chain fatty acids (SCFA).

Therefore, what is happening in the gut can directly influence our brain function and behaviour (4).

A schematic representation of the microbiota-gut-brain axis. Click to enlarge (38).

Summary: The gut-brain axis refers to the two-way connection and communication between the gut and the brain. What is happening in the gut can directly influence our brain function and behaviour.

The Role of the Gut Microbiome in the Gut-Brain Axis

Research has recently discovered a missing link within the gut-brain axis theory (5).

The latest theory involves the gut microbiome, which is an equally important part of the communication loop between the gut and brain.

The gut microbiome refers to the trillions of microorganisms that mainly live in the gut.

They are mainly comprised of bacteria, and it is these microbes that reside in the gut that directly communicate from the gut to the brain via the vagus nerve (6, 7).

Together, the gut-brain-microbiome axis is a complex interconnected circuit. This means that when an issue arises at any point within these communication loops, it can affect the whole system.

When this happens, a number of health conditions, such as IBS, depression, anxiety, obesity, autism and more may arise.

Summary: Recent research has found that the gut microbiome is also involved in the gut-brain axis. Any miscommunication between this three-way system can bring about a range of health conditions such as IBS, depression and anxiety.

The Gut-Brain Axis And Digestive Disorders

Changes in the communication between the gut, brain and gut microbiota may lead to the development of digestive disorders like IBS (8, 9).

IBS and the Gut-Brain Axis

For example, gut symptoms of IBS (gut part of the gut-brain axis) including bloating, stomach pain, wind and altered bowel habits is worsened by stress (brain part of the gut-brain axis) (10).

When under stress, the body’s in-built fight-or-flight response is activated.

The fight-or-flight response is the body’s natural survival reaction that occurs in response to a perceived threat.

When activated, digestion slows as the body uses its energy resources on the threat at hand, and in turn, increases gut sensitivity.

This was an important survival mechanism in the past as threats included events that were life-threatening, such as running from wild animals; however, in modern days, threats are likely non-life-threatening, such as meeting deadlines for work for school.

Unfortunately, the body cannot differentiate between types of stressors and responds in the same way.

As a result, gut function is altered and IBS gut symptoms of bloating, stomach pain, wind and altered bowel habits are worsened.

Another key feature of IBS that shows changes in the gut-brain connection is the presence of visceral hypersensitivity (11, 12).

Visceral hypersensitivity refers to a heightened perception of pain around the gut.

Simply put, it is an over-reactive response that comes from the gut to the brain, leading to an exaggerated perception of pain.

IBS and the Gut Microbiome

It’s still unknown whether changes in the gut microbiome are a cause or a consequence of conditions like IBS.

However, there’s strong evidence that the gut microbiome is different in people who have IBS versus those who don’t (13, 14, 15).

Studies have shown an imbalance in gut communities including both a reduction in the numbers and diversity of healthy microbes and an increase of potentially harmful microbes, collectively known as gut dysbiosis.

This difference likely plays a role in the dysfunction with the gut-brain connection.

Stress, which can make IBS symptoms worse, also changes the gut microbiome (16).

Studies have shown that even short-term stress can change the profile of the gut community, including lowering the amount of healthy bacteria like Lactobacillus (17).

Summary: Changes in the gut-brain-microbiome axis, caused by things like stress, can lead to digestive conditions such as IBS. This is due to activation of the body’s fight-or-flight response and changes in the gut microbiota.

The Gut-Brain Axis and Depression and Anxiety

The gut microbiota are a key regulator of the brain and behavior, influencing normal brain functioning and are involved in many psychiatric conditions including depression and anxiety (18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23).

Studies have found that there are differences in the gut microbiota of people who suffer with depression compared to those who don’t, and that this difference could be the cause of the onset of mental health conditions (24).

Just like in IBS, the gut microbiome is characterized with the presence of dysbiosis.

There is a reduction in both the diversity and total amount of healthy microbes in the gut of those who suffer with depression.

Summary: Dysbiosis in the gut microbiome is a direct factor that influences the gut-brain axis’ normal functioning and leads to mental health conditions like depression and anxiety.

Treatment Options

Fortunately, there are a number of treatment options that address the dysfunction of the gut-brain (and microbiome) axis.

Some key options include psychological therapies, diet therapy, probiotics, prebiotics and faecal microbiota transplant (FMT).

Psychological Therapies

Traditionally, there has been a predominant focus on psychological strategies to manage and reduce the stress response.

Examples include:

- Deep breathing – consciously breathing from the diaphragm (stomach area) rather than the chest, to mimic and induce the relaxed state of breathing (25)

- Cognitive behavioural therapy – this type of therapy focuses on modifying behaviours and alters dysfunctional thinking patterns to influence mood and physical symptoms (26)

- Gut-directed hypnotherapy – a new psychological therapy where suggestions are made for to control and normalise gut function (27)

These therapies essentially work to calm the mind and elicit the body’s relaxed state, which reduces the activation of the fight-or-flight response, and this improves mood and gut function.

Diet Therapy

More recently, there has been a significant shift towards manipulating diet to improve both mood and gut conditions (28, 29).

For example, a Mediterranean diet, which is characterized by a high fruit and vegetable intake, healthy fats such as olive oil and fish, wholegrains, legumes and nuts has been shown to increase the diversity of gut microbiota, which has a direct impact on the gut-brain-microbiome axis.

Another therapeutic diet, called the low FODMAP diet, restricts fermentable carbohydrates known as oligosaccharides, disaccharides, monosaccharides and polyols (FODMAPs), to reduce gut symptoms.

These FODMAPs are found in a variety of otherwise healthy foods including fruit, vegetables, grains, legumes and dairy. These foods are not tolerated well in people who suffer from IBS-like symptoms of bloating, wind, pain and altered bowel habits.

FODMAPs are fermented in the large bowel and this process causes stretching of the intestinal wall and stimulates nerves in the gut, triggering off pain and discomfort that is experienced by those who have IBS.

Thus, the restriction of FODMAPs reduces fermentation in the large bowel, reduces the stretching in the intestinal wall, limits the stimulation of nerves in the gut, and therefore also limits triggering off pain and discomfort in those who have IBS.

Both of these diets have been found to change the gut microbiota, which, as mentioned earlier, has a direct influence on the gut-brain axis and its normal functioning

Probiotics

Probiotics are defined as “ live microorganisms which when administered in adequate amounts confer a health benefit on the host” (30).

Probiotics can be found in fermented foods such as yoghurt, kefir, sauerkraut, and also in supplement form.

There are many different strains of probiotics that may have differing effects on the body, and they work by changing the gut microbiota.

It has been difficult to establish overall the effectiveness of probiotic supplementation due to differences in research methods used, however their use overall appears to be promising (31, 32, 33, 34).

A guide on probiotic strains and their specific effects can be found here.

The best probiotics to use in IBS has also been explored on this website and can be viewed here.

Prebiotics

Prebiotics are defined as “ “a substrate that is selectively utilized by host microorganisms conferring a health benefit” (35).

Prebiotics are largely found in foods high in fructo-oligosaccharides and galacto-oligosaccharides, such as wholegrains, onion, garlic, legumes, nuts, fruit and vegetables and are added to some probiotic supplements (36).

Essentially, they are food or fuel for the healthy gut microbiota to help them grow and thrive in the gut.

Improving the numbers and function of the gut microbiota through a high intake of prebiotics is another way that directly influences the gut-brain-microbiome axis and consequently gut health, behavior and mood.

Faecal Microbiota Transplant (FMT)

Another way to restore the gut microbiome is through a procedure called faecal microbiota transplant (FMT).

This involves transferring the faeces from a healthy donor to the patient suffering from dysbiosis to recover the impaired gut microbiota (36).

FMT has been used successfully in treating a range of health conditions including IBS, inflammatory bowel disease, autism and appears promising for the treatment of depression and anxiety (37).

Summary: There are various treatment options that target the gut-brain axis to improve functioning of the gut and the brain including psychological therapies, diet therapy, probiotics, prebiotics and faecal microbiota transplants (FMT).

The Gut-Brain Axis is Linked to Our Health

The link between the gut, brain, microbiome and our health is undeniable.

The gut-brain-microbiome axis is a complex network of pathways that communicates in all directions.

When communication within this axis is impaired, such as a change in microbiota (dysbiosis); health conditions like IBS, depression and anxiety may develop.

Treatment of these conditions is becoming more considerate of all three aspects of this axis including psychological therapies, diet therapy, probiotics, prebiotics and faecal microbiota transplants (FMT), as each one (gut, brain, microbiome) affects the next.

You can read more about using diet therapy to treat depression here or if you experience gut symptoms, then you might want to start by reading this article.